Engineering-17/12/2025

The Shape of Intelligence

Jonas Vetterle, Moonfire’s Head of AI & ML, closes out the year with a rumination on AI form factors and how we will interact with agents in 2026.

2025 has been dubbed the Year of Agents and, depending on what agent means to you, you are either positively surprised by the actual progress achieved this year, utterly underwhelmed, or anything in between.

Objectively, progress has been made - a lot. Compared to the general sense I got at the AI Engineer Summit in Feb, where people I talked to were working on anything from toy problems to production-ish applications, it feels like there is a lot more clarity now on what works and what doesn’t.

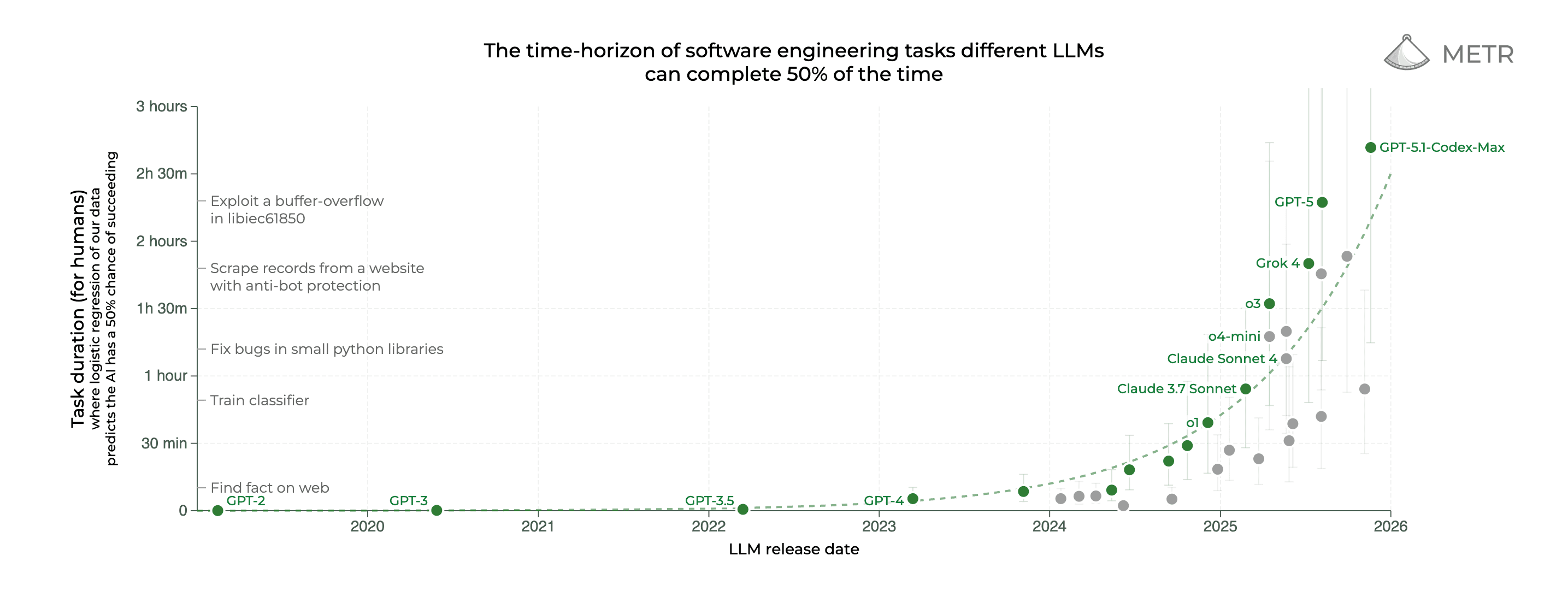

The prime example of agents that “work” is coding agents, which is unsurprising for a number of reasons, such as coding being a domain with verifiable results (e.g. deterministic compilers, test suites, linters), the modality being fundamentally text-based, and who the users are (software engineers).

However, even with coding agents, opinions are mixed depending on what your expectations were going into 2025. Andrej Karpathy thinks that, rather than 2025 being the year of agents, we’re in the decade of agents. The truth is: agents are just not solved yet, not even for coding, despite the value they bring today. Most people I know who are using coding agents day-to-day would agree with this. You cannot fully trust the code they produce. Common failure modes include agents failing on multi-file refactors and difficulty maintaining plan coherence over long horizons. That’s, of course, fine. I don’t fully trust the code anyone produces, and the need for code reviews remains, at least for now.

But, this leads to an interesting question of how we interact with AI today. Do you treat it as a chatbot where you read every answer and verify its correctness? Or, like a junior colleague who works on a task for a longer period before getting back to you? Or, like an entity with superhuman (or at least superior) capabilities, whose output you more or less trust?

This is a question not just about the performance of models, though this is part of it. It’s also a question about the modality we use to interact with an agent, about the duration that agents can do meaningful work for, the nature of the task, and how bad it gets when things go wrong. It’s about the degree to which agents are expected to follow instructions vs act autonomously, and ultimately the devices we use to interact with them, or the physical forms AI will take. When you start unpacking what that relationship looks like, a few core dimensions emerge:

- Interface modality (text, image, voice, video, physical motion?)

- Temporal scope (single interaction → long-running process)

- Task topology (error tolerance, reversibility, decomposability)

- Agency level (assistant → collaborator → autonomous unit)

- Embodiment (none → digital avatar → physical robot)

I summarise all of the above as the form factor of agents or the shape of intelligence (because who doesn’t like a catchy name?): the combination of interface, agency, embodiment, and temporal behaviour that defines how an AI system shows up to the user.

When Products Become Agents

To ground this taxonomy, it’s useful to look at how today’s dominant paradigm, transformer-based LLMs, shaped the first generation of agent interfaces. LLMs started becoming mainstream probably in 2022, when years of research and scaling culminated in the first consumer product, ChatGPT.

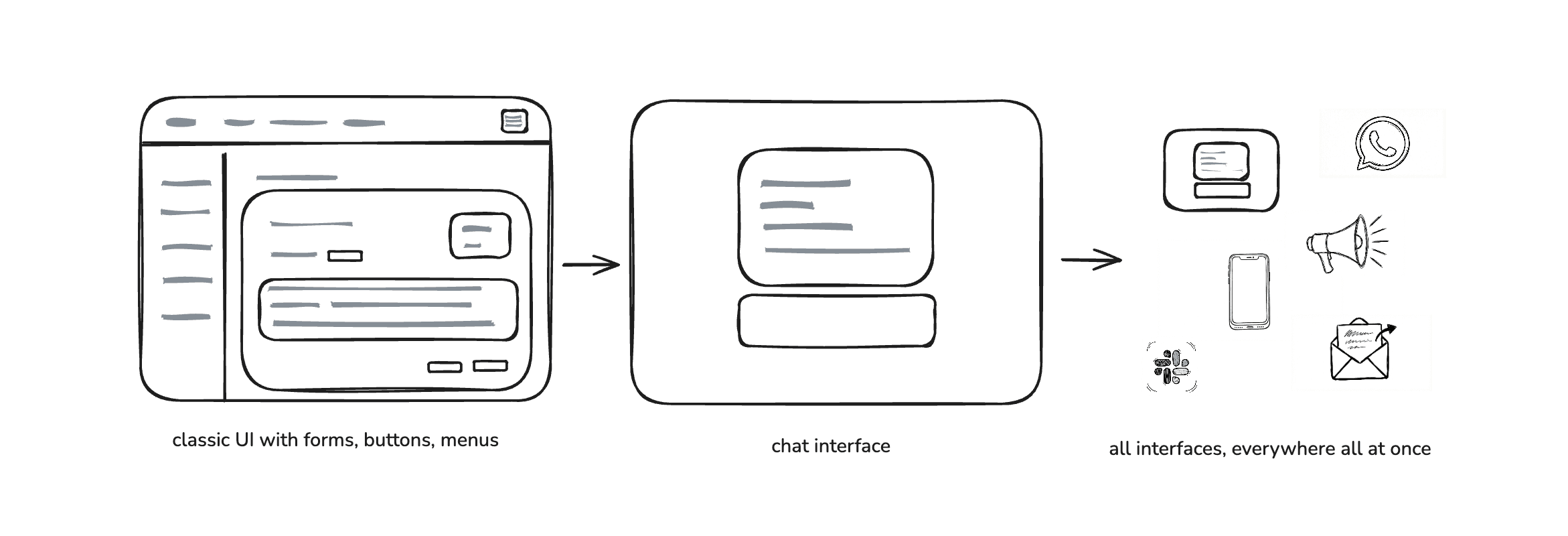

What we had back then was a question-answering chatbot, purely text-based, accessible via the browser, non-personalised and with no memory beyond the last couple of messages. Fast-forward to 2025, it’s increasingly clear that the chat interface was never the destination. It was simply the first stable form factor we stumbled into. Much of today’s software still forces the user into a traditional UI-driven flow where the user maintains the plan: you hold the mental model of what needs to happen next, and the UI exists to let you execute that plan one click at a time. In an agent-driven flow, this changes: The agent maintains the plan, updates it as the world changes, explains its reasoning and exposes only deltas: requests for confirmation, constraint violations, or ambiguous cases.

In that sense, agency shifts from execution to oversight. The workflow stops being something the user drives and becomes something the user supervises. This shift is subtle but profound: it means the primary surface of interaction moves away from dashboards and buttons toward goals, constraints, checkpoints, and exceptions. This redefinition of workflow surfaces isn’t theoretical — it’s already playing out in software development, where agents have begun dissolving the boundaries between tools.

The Fragmentation of the Interface

As was the case with copilots, software development tooling is leading the way, and gives us a glimpse into the future. It’s already the case that we can either write code ourselves, or delegate coding tasks to agents via the IDE, or via CLI tools like Claude Code, and interact with the same agents via web UIs to provide feedback, open PRs and so on. There is no single interface to write software anymore, and we can move more or less fluidly between those different interfaces. I believe this will increasingly become the norm in other industries too.

The form factor of intelligence is moving off the screen, out of the prompt, and into the substrate of workflows, devices, and environments. In the same way that you can talk to ChatGPT while taking a walk in the park, and then continue the conversation back home at your desktop, this will increasingly become the way we interact with AI and get work done. We will spend an ever decreasing amount of time in any particular UI and instead interact with AI across multiple modalities and devices. The way we get work done also changes from executing workflows ourselves to planning, giving instructions and approving/rejecting at certain checkpoints.

The UIs that remain will change from a place where we execute workflows to a control surface. There will no longer be a need for a “create invoice” button or a “trigger meeting preparation” menu. Instead, we will need a surface for defining high-level goals, constraints, approvals, notifications and debugging when things go wrong. By the way, this is also the ambition for our internal roadmap at Moonfire.

A prerequisite for this was the consolidation of tools. If the last couple of months were all about wrapping APIs into MCP servers and exposing them to an agent to use in a chat interface, the future will be about orchestrating work across any interface, in the same way you would collaborate with your co-workers.

What needs to get built

Delivering on this vision requires scaffolding around the models themselves: durable execution, memory, and orchestration layers that make agentic work reliable.

Agents for software development are both ahead of the curve in terms of capabilities and adoption, and also far from being solved. Even though the jury is still out on whether we’ll achieve “true generalisation” under the current paradigm, it’s plausible that for many use cases inter/extrapolating the training data will be good enough. The devil, of course, lies in the detail, or in the edge cases where agents often break, and where we need the review & approval interfaces mentioned above.

The first version of ChatGPT was entirely stateless, but now it remembers facts about you and state persists across sessions. It was also a ‘simple’ question-answer model, but now it can go away and do research for hours, and the trend for task duration knows only one direction (up). This kind of memory and durable execution will be crucial for the many-interfaces-across-many-devices scenario to work reliably. As is the case for continual learning, or the ability of models to learn new skills with minimal demonstrations.

Fore AI is building autonomous QA agents for enterprise software. Their agents rely heavily on memory to execute long, branching product flows - remembering past screens, expected outcomes, and partial progress so they can maintain coherence and resume work after interruptions. Memory isn’t just operational scaffolding; it also drives quality. When an agent has seen a pattern, layout, or behaviour before, it retains that context, making future runs more accurate and more stable.

Durable execution has real architectural consequences. Agents need resumable plans, idempotent tool calls, log-based state, and fault-tolerant orchestration capable of surviving crashes, network failures, and model updates. None of this comes for free from the LLM itself. Likewise, continual learning requires mechanisms for skill acquisition that don’t involve full fine-tunes: episodic memory, small adapter layers, tool induction, or lightweight domain-specific fine-tuning.

All of the above would benefit from net new research and better models, but even if there were no further improvements in foundation models, there is a lot that can be done on the product and engineering side to make progress. The future architecture for running agents, execution frameworks, memory systems, agent frameworks, etc, is still being built.

What happens around foundation models, the scaffolding is as, if not more, important. Latitude, who are building an AI engineering platform for product teams, believes that a reliable agent loop needs three things: instructions, tools, and feedback. With the three perfectly integrated, it feels like training an employee on a new task.

Our investments into Latitude and Mastra, who are building an all-in-one Typescript framework for AI-powered agents and applications, are both reflective of our belief in the potential of this problem space.

The road ahead

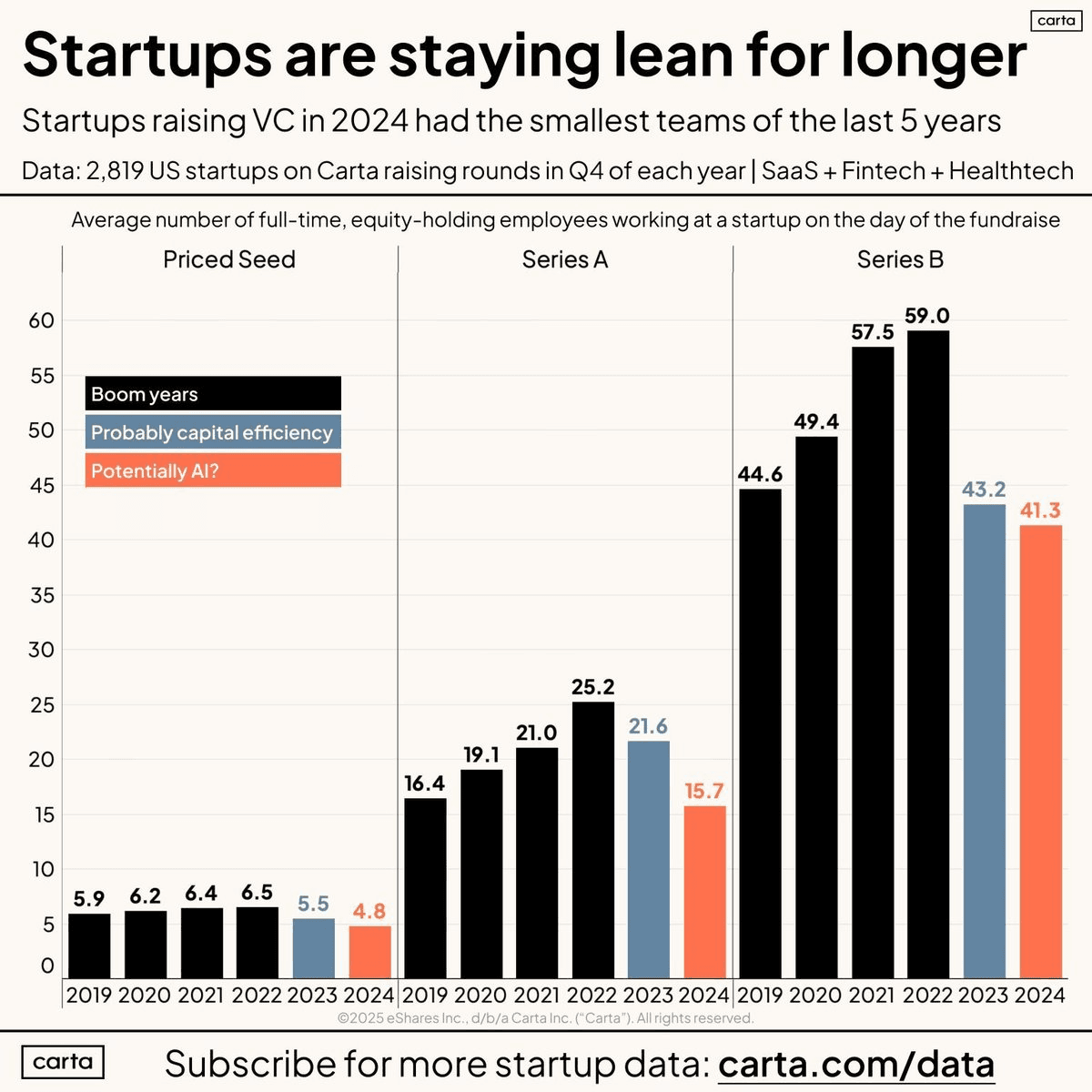

As agentic workflows mature, organisational structure adapts accordingly. If we extend this trajectory, it’s plausible to imagine a world of ever smaller teams, as work shifts more from doing to planning and supervising a team of agents. This is a trend that we can already observe in software engineering where the boundaries between backend and frontend engineers become blurred, and small teams can take on ever more ambitious projects. This could ultimately unlock the 1 person unicorn or, if taken to the extreme, fully autonomous business functions or even organisations.

Autonomous organisations emerge when multiple specialised agents share memory, coordinate through explicit protocols, and maintain role-specific objectives. Some functions lend themselves to this more than others, like account management, QA, and RevOps. These functions are already highly proceduralised, operate on structured data streams, and have clear escalation boundaries: ideal conditions for agent networks. As coordination overhead shrinks, human teams become orchestrators rather than executors, supervising a cluster of agents that operate continuously behind the scenes.

Kernel, who are building an agentic platform for Enterprise RevOps, Ambral, giving companies access to AI Account Managers to turn under-managed accounts into growth, and Fore AI, who are reimagining software testing using autonomous QA agents, are some of the companies in the Moonfire portfolio innovating in this area.

There is, finally, the most literal shape of intelligence: robots. The robotics form factor introduces constraints and capabilities that digital agents never face. Embodied systems require real-time perception, sensor fusion, continuous control, actuator-level decision-making, and strict safety guarantees under uncertainty. They operate in a world where latency matters, physics punishes errors, and affordances must be inferred from multimodal signals rather than described in text. Yet, paradoxically, the interface for robots may feel more intuitive: humans already understand turn-taking, pointing, gaze, spatial reference, and shared physical context. Once humanoid agents reach reliable grasping, navigation, and manipulation, interacting with a robot may feel more natural than interacting with a tabbed UI. Moonfire portfolio company Flexion is at the forefront of building the brain for humanoid robots.

Conclusion

As agents become more capable, the question shifts from what models can do to how intelligence should manifest. The form factor becomes the real design surface: whether intelligence appears as a chat interface, a persistent software worker, a coordinated network of specialised agents, or a robot acting in physical space. Each form factor reshapes the workflow, the user’s role, and ultimately the structure of organisations.

If the last few years were about making models smarter, the next decade will be about giving intelligence the right bodies, the right interfaces, and the right runtime. The shape of intelligence is changing and everything built on top of it will change with it.